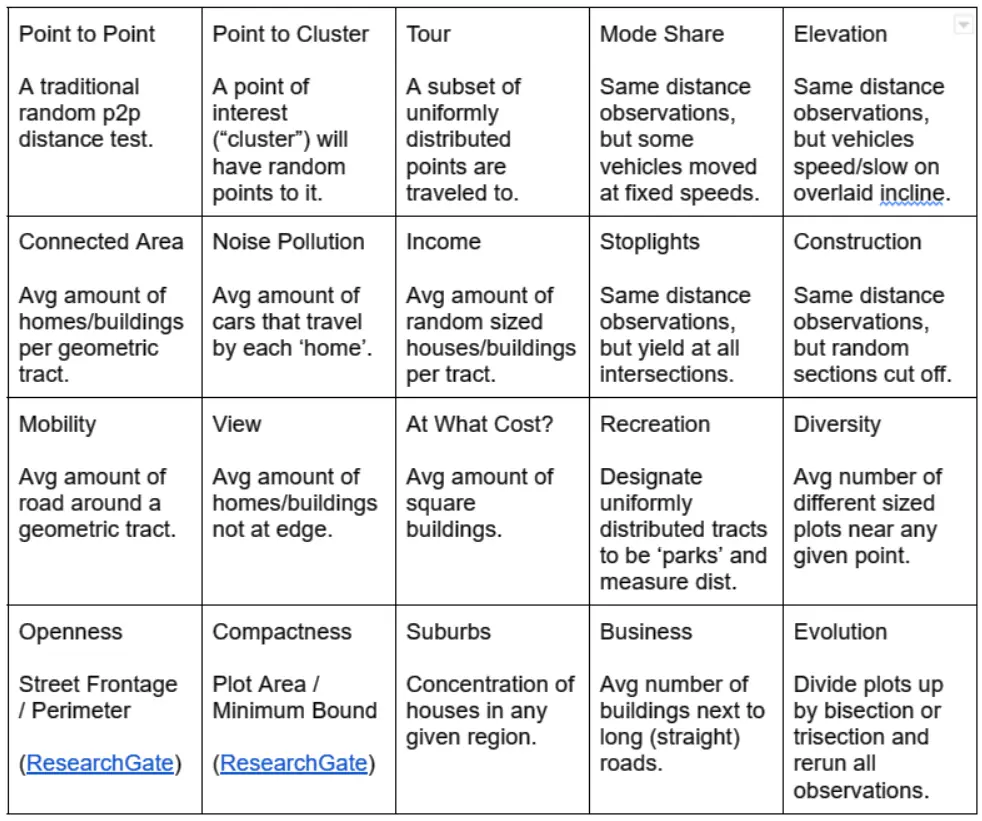

Urban Tessellations

Spatial Grids in Cities

Tessellations create uniform tiling of space with a geometric pattern—like squares or triangles repeating endlessly. We see similar patterns emerge in the urban environment: neighborhoods arranged on gridlines, highways scything through city blocks, and ad-hoc expansions that appear random. This project investigates whether traditional cubic grids (and other shapes) truly optimize aspects of city living—such as traffic flow, property sizes, and overall satisfaction—as "robot-designed" cities loom ever nearer.

We hypothesize that standard block-based layouts are suboptimal for modern city needs: limited elevation awareness, traffic bottlenecks, and an inability to handle high-speed transit. Building on research from traffic pattern analysis and morphological studies, we test alternative tiling systems—triangles, hexagons, Penrose patterns, or radial mosaics—to see how each fares under simulated conditions.

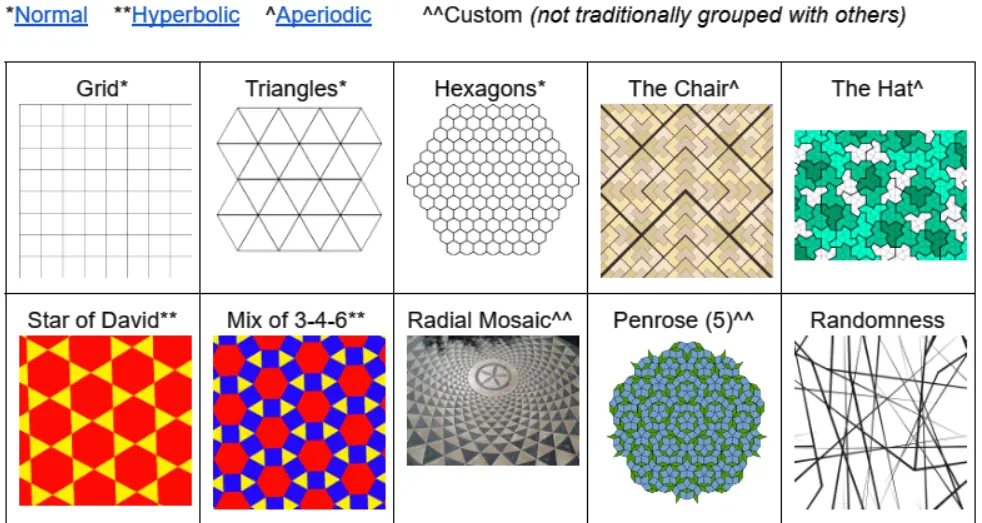

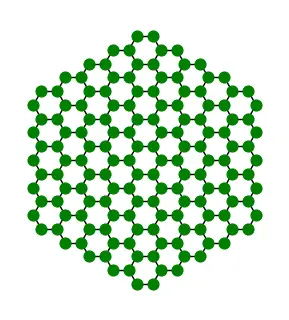

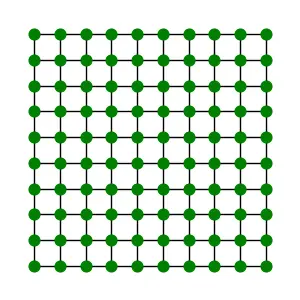

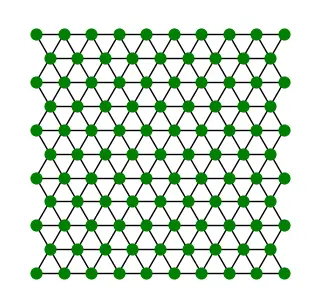

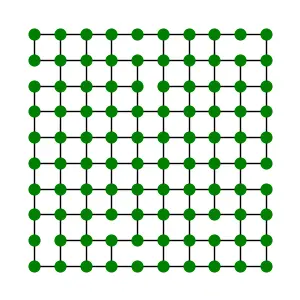

Tiling Examples

Below is a sample of four fundamental tessellations used in our experiments. Some are classically rigid (like squares), while others (like hexagons) might better distribute travel distances. We also include a random layout as a sanity check.

Hexagonal layout

Square layout

Triangular layout

Random layout

Approach

We identified key variables—like travel distance, slope/elevation impact, average building size, and even noise pollution—to compare the performance of each tessellation. Our plan involves simulating thousands of agent “vehicles” navigating the different layouts. Each agent follows certain graph rules to find the shortest or fastest route, with added constraints like random block closures or speed changes on slopes. Collectively, these data points yield insights into which geometry best balances all of our criteria.

We also incorporate specialized features such as highways or tunnels that pierce the grid, observing how these near-teleportation channels alter mobility. Our suspicion is that standard grids may underperform because they cannot flexibly accommodate new transport modes or extreme densities. Still, we remain open to the possibility that straightforward square blocks are surprisingly robust.

Results

Our early tests show that certain hyperbolic layouts handle steep elevation changes more gracefully, while radial or hex-based systems can reduce travel distance for a significant percentage of trips. Meanwhile, random sprawl sees drastic slowdowns in some corridors, with large void spaces remaining underutilized. We also noticed that introducing partial highways in a grid slightly improves throughput but doesn’t handle surges in traffic as gracefully as more flexible tilings.

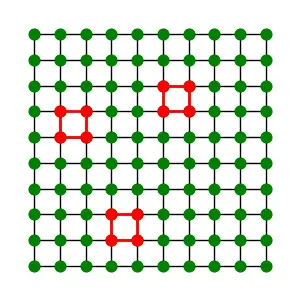

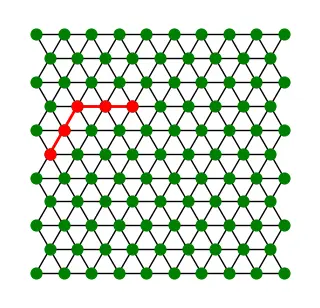

Below are a few example images that highlight different algorithmic examples, from cutting edges to highlight sub-block structures, to focusing on cyclical patterns that reveal bottlenecks. For performance, we perform simulations via graph theory, translating our tessellations into weighted graphs that agents traverse to find optimal paths.

Simulated Construction via Cut Edges

Identifying Traffic Cycles

Optimizing Random Point-to-Point Paths

Overall, these tessellations confirm that no single geometry is universally optimal. Each shape or approach, from squares to Penrose tiling, entails trade-offs in accessibility, buildable area, and traffic performance. Yet by mixing and matching key elements—like partial radial spines or layered highway/tunnel overlays—we can adapt designs to evolving urban demands. This tells us that it would be ideal to design neighborhoods with an X tiling, while highways and tunnels should be built in a Y tiling, with appropriate Z tiling for spaces that require a mix of both. For a more detailed breakdown, please refer to the code.

Future

Our simulations now pivot to analyzing morphological changes over time, toggling between short-term traffic data and long-term property expansions. We plan to incorporate live “agents” that represent devoplers or city planners. Each agent can subdivide blocks or propose new roads, further challenging the boundaries of any fixed tessellation. We also aim to evaluate how virtual reality might convey these spatial differences to stakeholders, bridging the gap between abstract geometry and tangible city life.