LLM-Based Compression

Language Models for Predictive Text Compression

Recent legal disputes—like the New York Times suing OpenAI—have put a spotlight on what generative text models "memorize." After all, if you can coax ChatGPT into spitting out a copyrighted article verbatim, does that essentially mean it's acting as a compression model for said text? We took that question literally and set about constructing a system where a large language model like BERT is trained to mask and reconstruct text, giving us a new compression method. Instead of counting on classical Huffman or dictionary-based methods, we exploit the language model's predictive powers to store less of our data and let the model fill in the blanks.

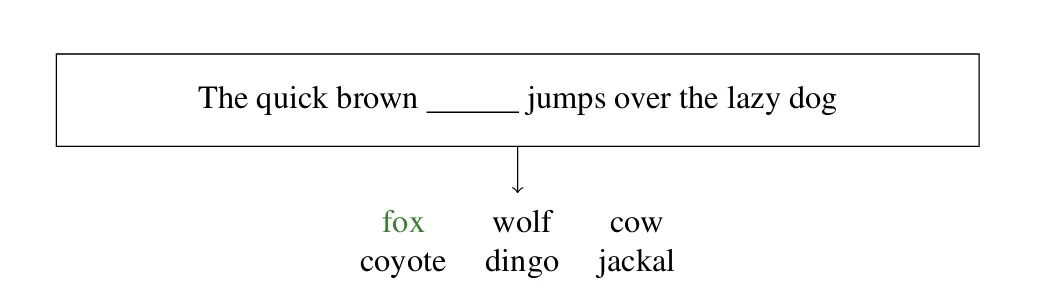

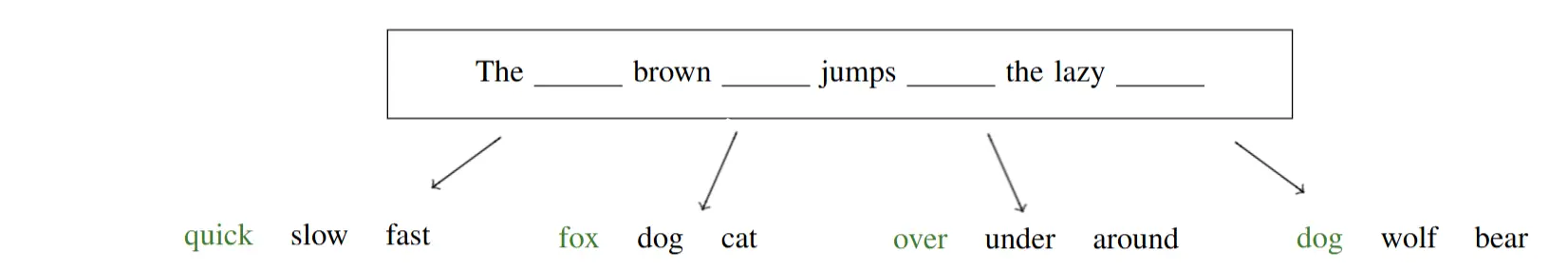

Compression has famously been seen as a prediction problem. If a model is capable of guessing certain words from context, we can store fewer tokens. So instead of storing every token in your Shakespeare corpus, we replace highly predictable words with a special mask token (and keep other tokens verbatim). At decompression time, the model infills those masks. If it does so perfectly, we get lossless compression. Otherwise, we accept a bit of text drift—we can call this fuzzy or lossy compression.

Method Overview

We start with a pre-trained BERT (or RoBERTa, DistilRoBERTa) and fine-tune it for masked language modeling (MLM). That's the classic approach where random tokens get replaced by [MASK], and the model learns to guess them from context. For compression:

- Fine-Tune for MLM: We tweak BERT so it's especially good at infilling masked tokens in the domain of interest (e.g., Wikipedia text).

- Mask to Compress: When we want to compress text, we mask a subset of tokens that the model should be able to guess easily. This subset's size controls our compression ratio.

- Decompress by Infilling: During decompression, we feed the masked text to the fine-tuned model, which reconstructs the missing words.

Rather like Huffman coding, we can take advantage of "predictable" words and omit them from the stored data. The model's knowledge effectively becomes part of our "dictionary," letting us store fewer bits. With enough training, it can come close to lossless reconstruction.

For short sequences, we can often outperform gzip due to the model's predictive ability. On longer sequences (like entire Wikipedia dumps), we see that even if our approach requires more epochs to perfectly guess 50%+ masked text, it can yield a nearly 2x compression ratio vs. classical methods. This is especially true as we mask more predictable words.

Experimental Results

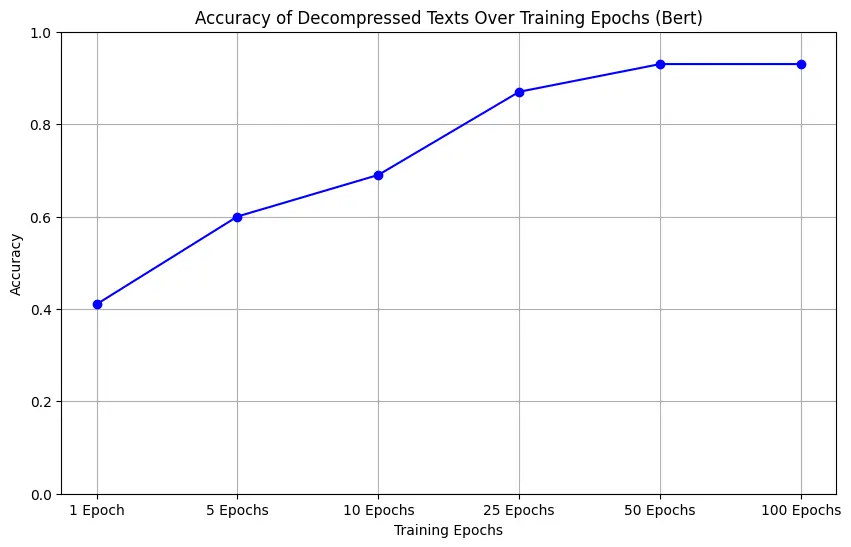

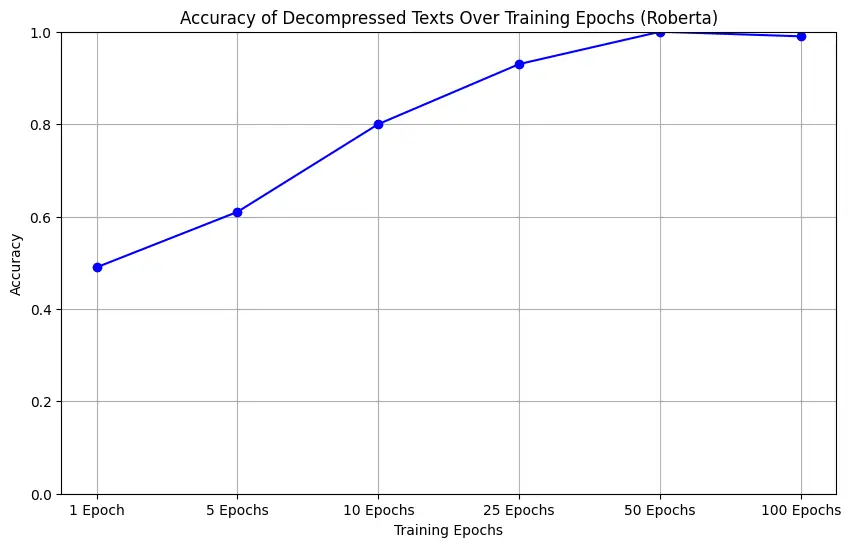

We tested BERT, RoBERTa, and DistilRoBERTa on short text sequences, fine-tuning them over varying epochs. The faster the model converges, the better we can guess masked tokens with fewer training steps. We also varied how aggressively we masked tokens (15%, 50%, or even purely deterministic masking, e.g., nouns/verbs only).

BERT reconstruction over multiple epochs

RoBERTa reconstruction trends

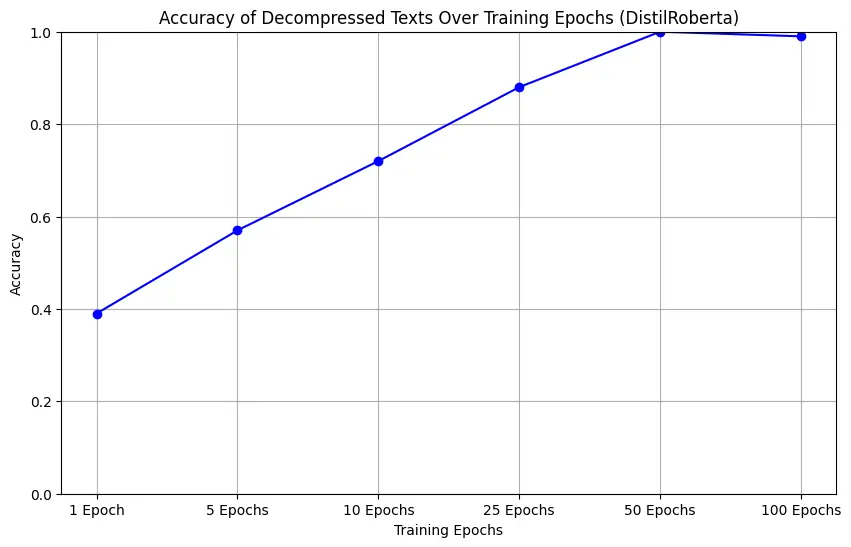

DistilRoBERTa reconstruction trends

Across the board, more epochs = higher fidelity decompression. However, RoBERTa can converge faster than classic BERT, and DistilRoBERTa offers decent performance for fewer parameters. Fine-grained tweaks—like masking only nouns/verbs or only easily predicted words—improved compression ratio while still hitting near-lossless reconstruction for short text sequences.

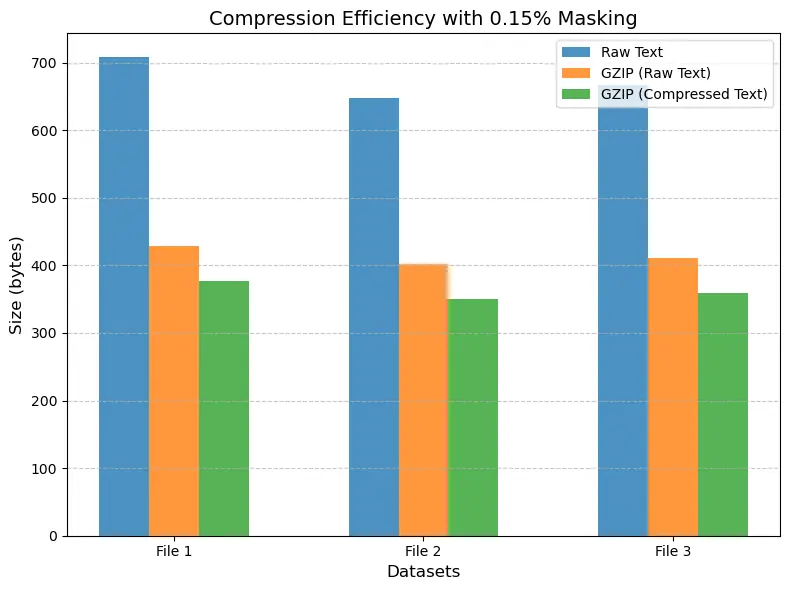

~15% masking can edge out gzip

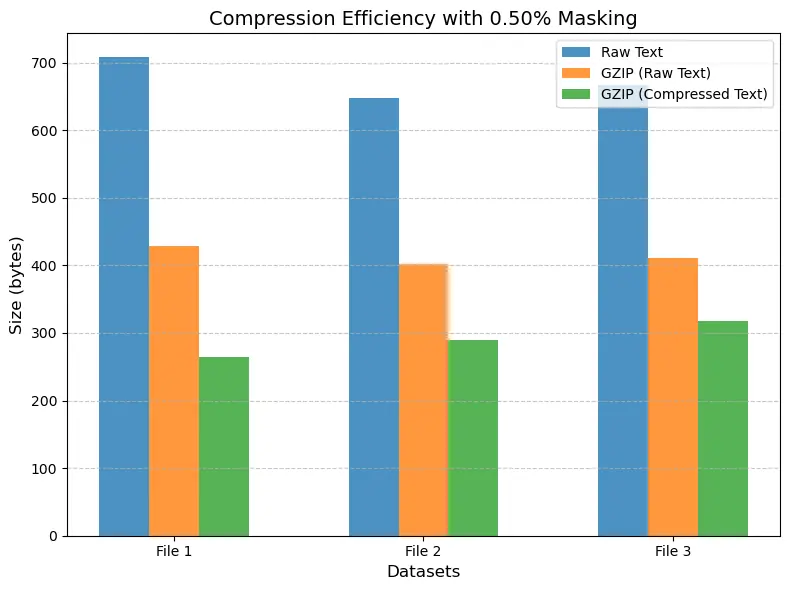

~50% masking can push ~2x reduction vs. gzip

Future

While the initial results are encouraging—showing LLM-based compression outperforms gzip on certain text sizes—this is only a start:

- Masking Strategy: We can mask words the model is "confident" about, rather than random selections, to push compression further.

- Entropy Coding: We could add an entropy-coded layer to reduce size even more.

- Scaling: Large models might easily restore text from heavy masking, but "carrying around the model weights" is non-trivial in practice.

- Images / Videos: Similar masked-then-predict logic might compress images or other data domains (with enough fine-tuning).

Our study offers a proof of concept that language models can, indeed, function as surprisingly capable "compression factories," letting us store (and then re-generate) data with fewer bits. The Times lawsuit was ironically a perfect impetus to investigate how much text is "memorized," which might point to a future where we can trade storage for compute.